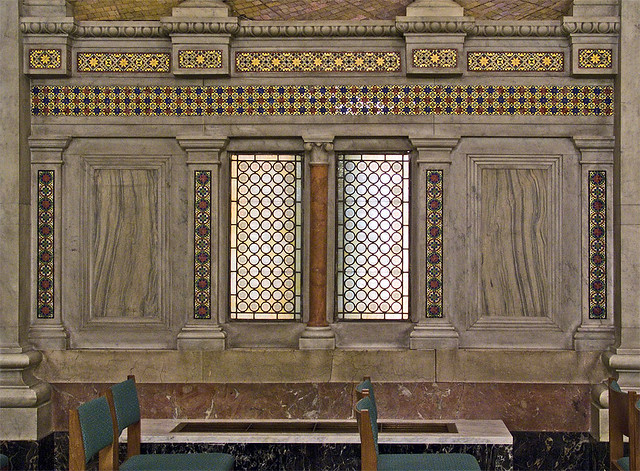

Ornament at the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis.

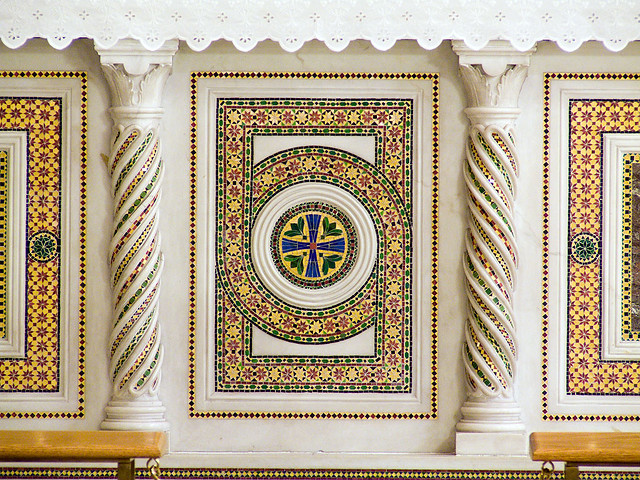

Ornament at the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis.

Architectural ornament was for decades a lost art in the West, which is a shame because it is beautiful, giving rest and pleasure to the eye, and it links us to cultures far into the past and across the continents. This loss is also unwarranted, because the principles of making traditional ornament are actually relatively simple — at least compared to figurative art. But perhaps the most important consideration is that the beauty of ornament flows from the underlying truth that it expresses, and so ornament can lift our minds upward towards more spiritual things.

I've long wanted to do an in-depth photo essay of the ornament at the Cathedral, largely because it is close to ground level and so easy to photograph. The figurative icons that are located 50 feet or more above are hard to capture because they are usually seen at odd angles from the floor, and so would likely need expensive equipment and intrusive camera work to photograph well. My problem was that the ornament here is found in such a bewildering variety that I had little idea as to how to approach it.

Fortunately, I found out that there is a mathematical classification of ornament based on its symmetry. These designs can be classified into groups, including symmetries of

reflection about a line,

rotation around point;

frieze groups which exhibit symmetries along a line;

wallpaper groups which have symmetries across a surface, helical symmetry on a cylinder, and so forth, in a logical, understandable, and orderly framework.

Nowadays, mathematics and art are opposed to each other — “drawing on different sides of the brain” according to a popular but discredited theory. But at one time it was not so.

It is surprising, perhaps, to learn that ancient and medieval art has a mathematical foundation, which reflects the mathematical order of the cosmos. Recovering this mathematical understanding is needed before we can recover the good use of ornament in architecture, based on first principles and not mere copying.

Dr. Brian Clair

Dr. Brian Clair, who teaches mathematics and computer science at

Saint Louis University, has web pages at

http://euler.slu.edu/~clair/cathedral, which illustrates the various classes of symmetries of ornament found at the Cathedral Basilica. Please note that the classification is quite abstract, and ignores the specific colors and the materials used in the ornament, but instead emphasizes their form. Recall Aristotle's

four causes: the most important are the formal cause, or design of an object, and the final cause or purpose for the object; modernity, on the other hand, emphasizes the material and efficient causes, which relate to the composition of an object and how it is made. It is easy to see how the modern emphasis can overlook ornament and its importance.

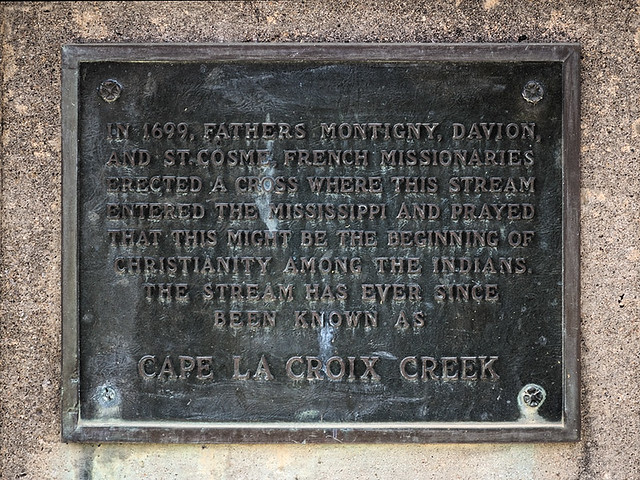

I frequently attend Mass and Confession at the Cathedral Basilica, and typically there are numbers of visitors there, for it is a popular tourist attraction. Invariably, these people are awe-struck at the massiveness and beauty of the interior, and we should not be surprised, because Catholic churches are intended to edify the masses.

These tourists snap innumerable snapshots, but alas, their photos are likely to be disappointing. In my early days of photographing the cathedral, I learned two important lessons in photography: subtracting out the color of the lighting from the image, and harmonizing the position and orientation of the camera with the subject. Some of these photos are old and aren't quite as harmonious as I would like.

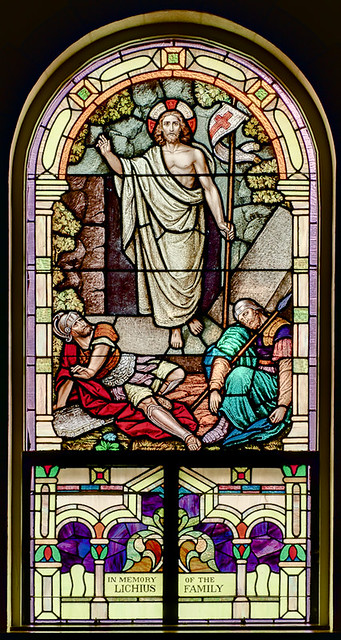

The Jewish Temple in Jerusalem had lush vegetative ornament, being reminiscent of Eden and the promised restoration of the garden of paradise at the world's consummation. Ancient synagogues often followed this pattern, as did the early Christian churches. Here we see peacocks, symbols of immortality, and two doves at a fountain in each corner, which among other things is a symbol of fidelity and baptism. We also have crosses.

Plainness and lack of ornament is associated with unorthodox sects, from radical denominations to Wahabbism in Islam, which tend to deny the value of the intellect and beauty, or which denigrate the value of the material world. Plain meeting-houses offer nothing for visitors, other than implying

“Begone! There is nothing for you here.” Their churches are necessarily uninviting, and they have few willing converts, for they do not

“Go into the whole world and proclaim the gospel to every creature.”

But a traditional church is inviting, asking visitors to stay for awhile, perhaps to pray, or even only to contemplate the beauty within, and so such a church ought to be open to visitors at all times.

Mathematics is traditionally seen as an important step towards enlightenment. Recognizing the underlying unity, order, and causes of things, rather than merely the immediate appearances of things is essential for intellectual — and ultimately spiritual — development. Expressing the mathematical order in works of art inspires not merely the passions, as is found in so much of contemporary art, but also inspires and helps to form the intellect.

The ornamentation at the Cathedral Basilica has a logical arrangement. The parts of the nave nearest to the main entrance and closest to ground level are more worldly, abstract, and more local, while as we rise upwards, and towards the sanctuary, the ornament is more heavenly, theological, and Christological. Finally the eye is drawn towards the high altar, depicting Christ suffering on the Cross, our salvation. But visitors to the nave are first presented with patterned geometric art, which lifts them above the mundane, ever-changing world, but in a manner that is perhaps gentler than Christ's battered and bloody

corpus.

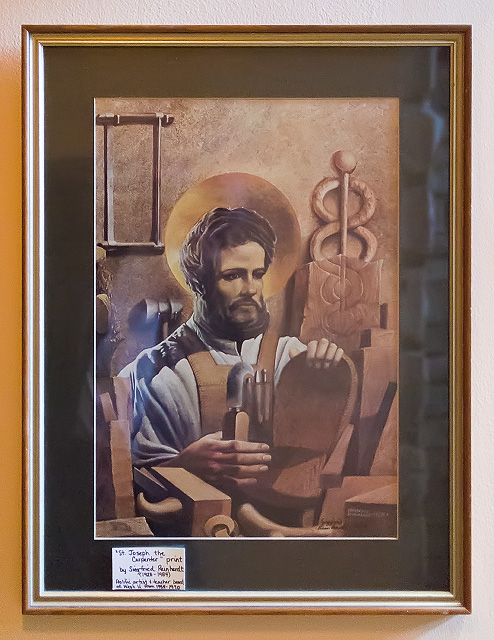

Ornament serves many uses. As the most important church in the archdiocese, it is fitting that it is most richly ornamented, and we would also expect fine ornament in a pilgrimage church, and so the amount and complexity of the ornament tells us of a building's importance. The ornament — including the iconic art — specifically tells us

what this building is, that it is a place of Christian worship. The ornament is festive and solemn, reflecting the liturgy offered here.

Mosaic work is a popular craft, but it is often done these days in a primitive style, lacking in geometric precision. Adding a basic knowledge of the various orders of symmetry, coupled with good skill in measurement and layout could easily restore this art, at least on a basic level.

More complex figures, such as the vegetative ornament as seen here, require a knowledge of proportion that is hard to find these days, and this may tempt artists to merely copy existing forms for new work. The problem with simple copying is that some designs, especially those that are highly ordered, are largely specific to the surface upon which they ornament. A different proportion of wall, for example, will require a different design pattern to keep a harmonious appearance, even if the basic elements of the design remains the same. The ability to adapt a type of pattern to new circumstances would require greater knowledge than the simple symmetries mentioned here. See the article

Abstraction and the “Grammar of Ornament” for some clues on how to do this.