UNION IN DISTINCTION makes order; order produces agreement; and proportion and agreement, in complete and finished things, make beauty. An army has beauty when it is composed of parts so ranged in order that their distinction is reduced to that proportion which they ought to have together for the making of one single army. For music to be beautiful, the voices must not only be true, clear, and distinct from one another, but also united together in such a way that there may arise a just consonance and harmony which is not unfitly termed a discordant harmony or rather harmonious discord.— Treatise on the Love of God, by Saint Francis de Sales (1567-1622)

Now as the angelic S. Thomas, following the great S. Denis, says excellently well, beauty and goodness though in some things they agree, yet still are not one and the same thing: for good is that which pleases the appetite and will, beauty that which pleases the understanding or knowledge; or, in other words, good is that which gives pleasure when we enjoy it, beauty that which gives pleasure when we know it. For which cause in proper speech we only attribute corporal beauty to the objects of those two senses which are the most intellectual and most in the service of the understanding—namely, sight and hearing, so that we do not say, these are beautiful odours or beautiful tastes: but we rightly say, these are beautiful voices and beautiful colours.

The beautiful then being called beautiful, because the knowledge thereof gives pleasure, it is requisite that besides the union and the distinction, the integrity, the order, and the agreement of its parts, there should be also splendour and brightness that it may be knowable and visible. Voices to be beautiful must be clear and true; discourses intelligible; colours brilliant and shining. Obscurity, shade and darkness are ugly and disfigure all things, because in them nothing is knowable, neither order, distinction, union nor agreement; which caused S. Denis to say, that "God as the sovereign beauty is author of the beautiful harmony, beautiful lustre and good grace which is found in all things, making the distribution and decomposition of his one ray of beauty spread out, as light, to make all things beautiful," willing that to compose beauty there should be agreement, clearness and good grace.

Certainly, Theotimus, beauty is without effect, unprofitable and dead, if light and splendour do not make it lively and effective, whence we term colours lively when they have light and lustre.

Pages

▼

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Saint Francis de Sales on Beauty

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Newsletter from the Oratory

| View this as a web page. | ||||||

|

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Downton Abbey Presentation at the Belleville Cathedral

From Saint Peter's Cathedral in Belleville, Illinois:

"Downton Abbey"

and

Christian Morality,

Christian Family

and Christian Society

Presentation and Discussion

with selected scenes from the series

Thursday January 31

7:00 pm to 8:30 pm

in the Undercroft

of St. Peter's Cathedral, Belleville

Monsignor John T. Myler, Rector:

"There are many, many fans of 'Downton Abbey' in our parishes and congregations. And although there is very little discussion of God in the series -- maybe a little praying or an occasional wedding in a church -- the stories seem to be a reflection of tested faith and hope in times of hopelessness: world war ... unjust imprisonment ... the loss of job or fortune ... the complexities of family life."Free admission. Open to all.

"The stories of the characters 'upstairs' and 'downstairs', the stories of their personal struggles, of upheavals in the family and in society, all demonstrate what a modern-day crisis-of-faith is often like."

"I think that's why so many people around the world find 'Downton Abbey' so interesting."

Part of the Cathedral's on-going "Adult Faith Formation" series.

Wednesday, January 16, 2013

On Analogy

THERE ARE SEVERAL common modes of human reason, which includes the familiar processes of inductive and deductive reasoning, as well as abductive reasoning, hypothetical reasoning, and others.

But one of the most powerful modes of reasoning — if not the most precise — is analogical reasoning, where you compare and contrast one sort of thing to another. Inductive and deductive methods are rather precise, but can be slow, plodding, expensive, or difficult, and we can often end up with trivial results such as “Oceans are determined to be very large and full of water.” However, analogical reasoning takes the full capacity of the human imagination to quickly jump from one thing to another, which may lead to unexpected and novel results. For example, Niels Bohr developed a model of the atom, analogizing it with the solar system, which led to a new understanding of nature. Some think that analogical reasoning is the base or primary mode of reasoning of the human intellect, since it contains within it aspects of all the other modes of reason. Analogical reasoning is very fruitful: it proposes, and the other more precise modes of reasoning fills in the details; perhaps deduction and induction are not possible without first making the analogy.

Examples, parts, or close relations of analogy include:

...exemplification, comparisons, metaphors, similes, allegories, and parables, ... association, ... correspondence, mathematical and morphological homology, homomorphism, iconicity, isomorphism, ... resemblance, and similarity....In the field of artificial intelligence, it was originally thought that computer systems based on pure deductive reasoning would lead to a human level of intelligence, but this did not work out in practice, and it seems that research on this has been moribund since the 1980s. However, a newer computer algorithm, the Vector Space Model, uses analogical reasoning and has nearly achieved the average human level of performance on the College Board's SAT multiple-choice analogy test. Analogical reasoning is used effectively in Google Search, which often produces surprising yet reasonable Internet search results.

Some of the powerful analogies include arguments from symmetry and proportion. Indeed, the English word “analogy” derives from the ancient Greek ἀναλογία, analogia, meaning “proportion”. We say that the proportions 3:2 and 6:4 are analogous since they have the same ratio of 1.5, and likewise we can analogize by saying that fingers are to the hand as toes are to the foot. The Greek philosopher Plato used his allegories as analogical arguments, as did Our Lord in His parables. Analogy is particularly important in the figurative arts, where we associate daubs of paint on a canvas with say, a human face. Biologists use analogy extensively when comparing the anatomy of various species, and have thereby discovered the principle of convergence.

Good analogical reasoning not only compares similarities between two things, but also contrasts their differences. When Bohr developed his atomic model, he reasoned that the tiny electrons orbit around a large nucleus, as the planets orbit around the sun. But on the atomic scale, quantum effects predominate, and so the analogy breaks down a bit, since it is hard to claim that the electrons are actually orbiting, and so this needed a better mathematical model. But one of the great benefits of analogical reasoning is that the things that we learn about a new unfamiliar system (such as the atom) can shed light back upon the old familiar system (such as the solar system): some of the newer mathematics that explained the atom, in turn, can be analogously used to more fully explain the solar system.

Some claim that analogies are methods used by those in power to impose meaning, and this could happen, and so analogies have to be made intelligently to be truthful and fruitful. An old model of the atom, called the ‘plum pudding model,’ did not bear (or even contain) fruit, although it does sound tasty: but it is an absurd analogy. A good analogy must highlight any differences that exist, as well as similarities, otherwise it indeed is an imposition of meaning. It seems that a good analogy must start with something baser, and then go by analogy to something higher. Modern political discourse will often attempt to analogize a current political issue with something Biblical, such as the Jews' exodus from Egypt. Since this is an inversion of the hierarchy of importance, this trivializes scripture and tells us nothing new, and so we aren't learning anything: where, according to the politicians, are the Commandments of God? Lest we forget, new knowledge is the goal of reasoning. Our Lord's parable of the Prodigal Son indeed starts with something common — a father's forgiveness towards his wayward son — but instead points to the greater meaning of God's forgiveness for our sins; while this analogy tells us something about the relationship between human fathers and sons, that is not the main point of the parable, which mainly reveals to us knowledge of God.

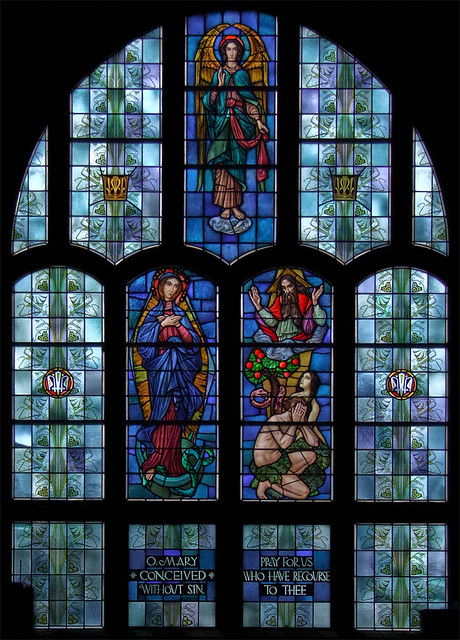

Analogy is of great importance in Catholic and Orthodox Biblical exegesis — the interpretation of scripture — and this forms the basis of what is called Biblical typology. A ‘type’ in ancient Greek is a small model which is made by an artist in preparation for his larger final work of art (we still use this sense in the English word prototype), and so what God made in the Old Testament can seen as types, figures, or models for what we find fulfilled in the New Testament. We find many striking similarities in events and persons between the Old and New Testaments, and by using analogical reasoning, we can compare and contrast these, seeing the Old Testament types as models or foreshadowings of what is to come. We often find that something in the Old Testament reveals something in the New, and that what is found in the New Testament more fully explains the Old. We are told, explicitly, that the lamb slaughtered on Passover is a type of Christ, and in turn, Christ reveals more clearly the meaning of the Passover. The lovers in the Song of Songs analogously show the relationship between God and the human soul, which is something that was long recognized by the ancient rabbis, but can also be seen as a type of the relationship between Christ and the Church, and the Holy Spirit with the Virgin Mary. Through analogy, we see that Eve is a type of Mary, and so the Virgin is called the New Eve, and the main contrast illuminated by the analogy is that Mary succeeded where Eve failed.

Analogical reasoning applied to sacred scripture is also used in moral theology as well as in eschatology. We also find much analogy in the liturgy: the Old Testament reading at the Mass often prefigures the Gospel reading, and the Roman Canon explicitly mentions various Old Testament figures:

Be pleased to look upon these offerings with a serene and kindly countenance, and to accept them, as once you were pleased to accept the gifts of your servant Abel the just, the sacrifice of our Abraham, our father in faith, and the offering of your high priest Melchizedek, a holy sacrifice, a spotless victim.

A stained glass window depicting Mary and Eve, at Immaculate Conception Church in Union, Missouri, illustrates the typology of Mary being the New Eve.

These analogies are of great importance to understanding Catholicism in general, and even when understanding Catholic art, where we might see the sacrifice of Abraham juxtaposed with the Crucifixion, or Melchizedek juxtaposed with the Last Supper. A flat, exclusively literal reading of sacred scripture — while not being denied by the Church, which is very important — tends to be dull, plodding, and disconnected. Reading the analogies in scripture brings it to life. Also, analogous reasoning can also be applied to nature, where natural objects such as water and light (which can be used to wash us or to light our way) give us spiritual insights, and in turn, we find that natural things such as water can have a sacramental role as in baptism.

We also find that analogical-typological reasoning can be useful for analyzing secular works. In the novel The Lord of the Rings, the characters of Gandalf, Frodo, and Aragorn, are each seen to be Christ types, being analogous to Christ's threefold office of prophet, victim-priest, and king respectively, and the plot of the novel can be better understood in this light. Analogies between secular Roman works on love and sacred scripture have also proved to be fruitful: the Romans discovered that jealousy is necessarily found in a lover, otherwise he does not love, and this shows to us the Biblical claim that God is jealous is likewise necessary, otherwise He does not love us; the Faith then more fully illuminates the classical notion that love has a Divine source.

In general, failure to observe analogous situations tends to set up an intellectual opposition between things, leading to ideologies. Scientism, for example, is an ideology that claims that the inductive method is the only valid form of reasoning, and this in turn ends up denying cause and effect. In religion, some see the Old and New Testaments as being in opposition to each other, which is core idea behind Gnosticism and ideological anti-Semitism; but this makes analogy impossible and so destroys the full Christian understanding and has unfortunate implications. Without good analogizing, things are seen in conflict which ends in destruction, and indeed we find a great distrust of analogy in Marxism, which is the ideology responsible for the greatest shedding of blood in human history. Analogy, on the other hand, tends to unify knowledge, and so in turn may help unify and harmonize society.

Starting on Wednesday, January 23rd, 2013, Dr. Lawrence Feingold will deliver a series of lectures at the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis, “Typology: How the Old Testament Prefigures the New,” where he will demonstrate the fruits of the Church's typological understanding of sacred scripture. More information can be found here, and the outline (and eventually, God willing, audio recordings) of the lectures can be found here. Some of Dr. Feingold's previous lectures on typology can be found here and here.

Also, you might want to visit the exhibit Federico Barocci: Renaissance Master at the Saint Louis Art Museum, which runs through January 20th, 2013. The exhibit is free on Friday. In addition to devotion-inspiring large religious paintings by a little-known but excellent artist, the exhibit includes many fine drawings that are models or types that Barocci used before making his finished work.

Monday, January 14, 2013

A Night Hike to the Confluence

ON NEW YEAR'S EVE, I participated in a special night hike at the Columbia Bottom Conservation Area, managed by the Missouri Department of Conservation. Our destination was the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

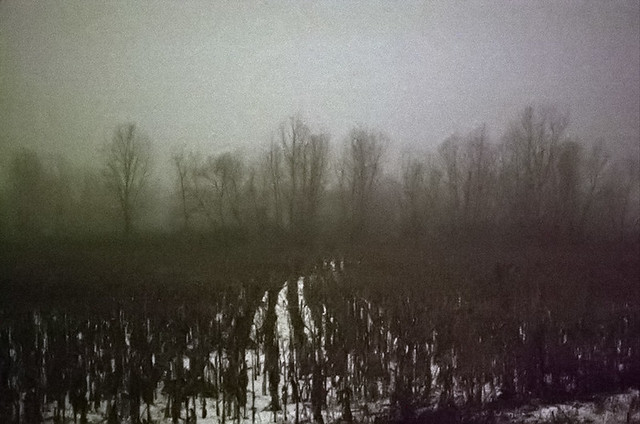

It was a dark, moonless night, but overcast skies reflected distant artificial lighting, making photography possible. But I could not use a tripod, since I had to keep up with the other hikers, and so these images are severely underexposed and rough.

From the hum of the Diesel-powered tugboats on the nearby rivers, to the dull whine of jets coming in for landing at Lambert Field, we knew that we were close to civilization. But adjacent to more than 4000 acres of forest and fields, and we were also undoubtedly in wilderness, as the howling packs of coyotes did remind us.

An impressionistic view of bare trees in the fog and fields covered with snow.

Broad daylight is about 2 million times brighter than what we see here. All the camera can capture with a reasonably short exposure time is not that much unlike what is seen by the eye: vague detail, uncertain color. Were this not flat bottomland with paved trails, traveling like this in the dark would likely be dangerous, for footing is always uncertain.

In the natural order of things, hiking at night can lead to a sense of humility when a person recognizes their limitations, and it can also lead to the virtue of courage, as a person pushes himself onward despite not being able to see the way clearly, despite the dangers found in the darkness. Admittedly, this night was not particularly frightful at all for most of us, but perhaps it is good training.

In the spiritual order, it seems that all major religions and philosophies — including Christianity — recognize that light is a natural symbol of truth, understanding, purity, and ultimate reality. Christ describes himself and his disciples as the light of the world. And so, darkness is a symbol of ignorance, sin, and death. We find this in the 12th century Aberdeen Bestiary, where it describes the symbolism of the owl: “In a mystic sense, the night-owl signifies Christ. Christ loves the darkness of night because he does not want sinners — who are represented by darkness — to die but to be converted and live.”

The state leases the land to farmers; the farmers, in exchange, leave behind a tenth of the crop for the feeding of wildlife. The land here is exceptionally fertile, but flooding is always a frequent risk. The idea of leaving food for wildlife is now common and unremarkable, but the older Biblical command to allow gleaning by humans (which was also the law in England until 1788) is now unthinkable.

Some of this land was once owned by Jacques Marcelin Ceran de Hault de Lassus de St. Vrain (1770-1818), a former French naval commander, who fled the Revolution for the relative safety of the Spanish colonies here in North America. He and his family settled in the Spanish Lake area, located on the uplands overlooking these river valleys, and he served in the king's navy by patrolling the rivers.

Hikers arrive at the destination, a monument to the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery, which includes interpretive descriptions of these great rivers.

Water levels are extremely low, and the normally swift current of the Missouri, seen in the foreground in front of the point of land, appears placid. The Mississippi River, seen behind the point, continues downstream to the right.

The first known European explorer of this area, Jacques Marquette, S.J., described this confluence of the rivers in his journals:

“While conversing about these monsters, sailing quietly in clear and calm Water, we heard the noise of a rapid, into which we were about to run. I have seen nothing more dreadful. An accumulation of large and entire trees, branches, and floating islands, was issuing from The mouth of The river pekistanouï, with such impetuosity that we could not without great danger risk passing through it. So great was the agitation that the water was very muddy, and could not become clear.”The monsters he mentioned were paintings on the bluffs upstream from here. The city of Alton's well-known symbol, the Piasa Bird, was inspired by these native paintings.

These days, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers keeps the stream largely free from floating logs — although these still dangers, and so having a steel-hulled boat on this river is greatly recommended, to avoid being foundered by submerged snags. Very little pleasure boating is done on this stretch of the Missouri. The river is still exceptionally muddy, which gave rise to the saying that the Missouri is “too thick to drink and too thin to plow.” The Mississippi upstream from the confluence remains placid and fairly clear to our present day, and is popular for sailing. Click here for an aerial map of the area.

The tall structure across the river in Illinois is the Lewis and Clark Confluence Tower.

Guide searches for wild animals. We saw many footprints of various creatures in the snow.

Click here for more information on the conservation area.

Monday, January 07, 2013

George Will and the Problem of History

RECENTLY, I attended a lecture given by political journalist George Will, in Graham Chapel at Washington University in Saint Louis, where he argued favorably about the importance of religion in civic life. Following a glowing introduction from former United States Senator John Danforth, Mr. Will, despite being a prominent conservative, received a warm reception from the crowd in this university known for its liberalism. Will's style is professorial and not argumentative, and he presented his case using factual evidence, not lowering himself to using ad hominem attacks; in his genteel manner, he seems much like his mentor, the late William F. Buckley, Jr., and rather unlike the conservative — but quite confrontational — talk show host Rush Limbaugh.

Graham Chapel, the venue for the lecture. Although called a chapel, this building is not set apart for sacred worship, but is used mainly for concerts and lectures. The university was founded by liberal Protestant clergy and wealthy businessmen. More of my photos of architecture on the campus can be seen here.

Will talked about how progressivism differs from conservatism. Initially he focused on the person of Woodrow Wilson, president of the United States (1913-1921), and leading Progressive, who radically expanded the role of government in the republic. According to Will, the Founding Fathers of the country feared the tyranny of majorities in a democratic state, and so placed in the Constitution a system of checks and balances to protect the rights of minorities. According to Will, thanks to the writings of Niccolò Machiavelli, Martin Luther, and Thomas Hobbes, the author of the book Leviathan, the Founders knew how to put together a good government (despite all three being highly problematic authors, especially for Catholics). It seems that history, to George Will, started in the Renaissance, and nothing from the age of Christendom seems to be of value to him. The progressives however, ignore history as irrelevant, and thought that the process of evolution, shaped by democracy in the U.S., had bred-out the bad tendencies of human nature, and that there should no longer be a fear of the majority or of strong leaders.

Mr. Will repeated the belief of the Founders that a good republic rests on civic morality, which is promoted by religion, and therefore we ought not fear the influence of the religious on political culture. England, he noted, was ravaged cheap gin, but it was not politics but rather John Wesley and Methodism that saved her. Will — when responding to a comment about the possibility of the religious Right turning the U.S. into a theocracy like Iran — stated that religious conservatives in the U.S. traditionally are ‘quietist’ regarding politics, until they are forced to become politically active to protect their rights. Indeed, religion once had an influential role in the political life of the U.S., but led by liberal Christians such as Wilson and Martin Luther King.

But to Will, an agnostic, it seems that any religion will do, and he backed up his belief in indifferentism by a number of quotes from the Founders. [However, a friend of mine who also attended the lecture knew of contradictory quotes from the same men, who rather seemed to think that any Christian religion would do.] Recall that the Founders feared the tyranny of the majority: they particularly feared a majority of any particular religion; so while they promoted religion in general, they wanted a radical Protestant kind of religion, one that was unorganized and chaotic, and therefore, not a threat to the State.

Religious liberty is often promoted as a core belief of the American republic, but precisely what this liberty means to the political elites of the country is questionable. The Left typically defines this as ‘freedom from’ religion, similar to the French policy of laïcité, which seeks to free the people from the burdens of morality and “superstition,” which we see here. To the Left, it is the duty of religion, if it is allowed to exist at all, to conform to the desires of the State, and the State is more than willing to regulate or exterminate religions to reach these goals.

But the attitude of the elites of the political Right, if we consider Mr. Will's opinions to be common, is more benign but also harmful. To them, the role of religion is limited to building up the civic virtue of the citizenry, and so therefore is a means to an end instead of something valuable in itself, and as we have seen, no one religion is allowed to become an majority. It appears that a divide-and-conquer strategy is used often, typically by splitting religions along political lines, as has occurred often in U.S. history. Christ, who is the same yesterday, today, and forever (Heb. 13:8), is instead seen as a changeable political hack.

Both the Left and Right encourages infiltration of religions: nonbelievers are strongly encouraged to be members of a church, and to take an active part in governing them, despite their lack of faith. This is seen as being respectable, traditional, or even conservative or progressive according to various viewpoints. In my youth, I even recall government-sponsored public service announcements that encouraged people to “attend the church or synagogue of your choice.” Historically, the non-believer Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were regular church attendees, as is our current president, who according to his autobiography is also a non-believer. Former presidents Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter actually started their own religion, the New Baptist Covenant, although I know nothing of these men's religiosity. However, the most conservative president in recent memory, Ronald Reagan, did not attend church at all. Coldness is perhaps better than being lukewarm (Rev. 3:16)?

The U.S. is a good place to be a member of a small or fringe religion, for the kind of freedom of religion found here allows small groups to flourish with little explicit pressure either from government or from the culture in general. Orthodox Christians, Jews, small Protestant sects, and even New Age religionists find themselves here a pleasant land where they can do as they will. Unlike other countries, they do not have to register with a department of government (although they might have to submit paperwork to be recognized as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization), nor do they normally have to deal with hostile, violent crowds.

But what is good for a small religion does not work for Catholicism, which claims universality. Offering services once a week is a simple thing that is barely regulated (unlike what is found in Canada or China). Doing other things, things which we are compelled to do out of love of neighbor, such as education and health care, are not so simple, and the State has been grasping for these, first with the public schools and now with the health care mandate. In this, conservatives and progressives agree: the Church must be restricted. Be aware that the state cared little about these until the Church brought them to these shores, and the public school system was created specifically to counter the Catholic schools. But as Catholic schools declined, the state-owned schools also declined with them, and if Catholic hospitals are allowed to fall, then health care in general will also fall. Few of those who rule the State know why these things are good and what they are for. Reproductive ‘health’ (meaning abortion on demand) and the economics of chronic health care are not valid or moral reasons for state control of hospitals.

Many traditional Catholics long for the days when powerful monarchs, such as the Kings of France and Spain actively promoted the Faith, especially since atheistic regimes now rule much of the world. But realize that these monarchs often tightly controlled the Church, by appointing her bishops and regulating her religious orders, and the situation was even worse in Russia, where the Tsars took over the role of the local Patriarch of the faith. When atheists took control of those states, they continued the policies of state control over religion. Even to this day, the secularistic government of France has a role in the selection of Catholic bishops.

In history, the ultramontanes strongly supported the role of the Papacy over local sovereigns. But some asked, why should Catholics support a weak Pope when they had a king who was powerful enough to get things done? We find this attitude even among the faithful today, putting too much trust in the princes and powers of the world. But the ultramontanists were right, as was affirmed by the First Vatican Council. An unrooted Christianity will soon find itself subverted to one political ideology or another, even in the United States, but an ultramontane attitude, leading to an integral and activist Catholicism, is the best remedy.

“The Adoration of the Magi”

“BEHOLD,” says Our Lord, “I make all things new” (Rev. 21:5). Redemption applies not only to our souls, but also to our works — transforming, even, our works of art. This is evident in the art of Christendom, long in decline, but now experiencing a revival. “...The riches of the sea shall be emptied out before you, the wealth of nations shall be brought to you...” (Isa. 60:5), so says the first reading for the liturgy of the Epiphany, and with a humble, obedient faith, these riches can be put to good use, even in art:

Man, if he tries to be a god in his art, makes a fool of himself. He becomes like God, he makes beauty like God, when he is too much aware of God to be aware of himself. Then only does he not set himself too easy a task, for then he does not make his theme so that he may accomplish it; it is forced upon him by his awareness of God, by his wonder and value for an excellence not his own. So in all the beauty of art there is a humility not only of conception, but also of execution, which is mere failure and ugliness to those who expect to find in art the beauty and finish of nature, who expect it to be born, not made. They are always disappointed by the greatest works of art, by their inadequacy and strain and labour. They look for a proof of what man can do and find a confession of what he cannot do; but that confession, made sincerely and passionately, is beauty. There is also a serenity in the beauty of art, but it is the serenity of self-surrender, not of self-satisfaction, of the saint, not of the lady of fashion. And all the accomplishment of great art, its infinite superiority in mere skill over the work of the merely skillful, comes from the incessant effort of the artist to do more than he can. By that he is trained; by that his work is distinguished from the mere exclamation of wonder. He is not content to applaud; he must also worship, and make his offerings in his worship; and they are the best he can do. It was not only the shepherds who came to the birth of Christ; the wise men came also and brought their treasures with them. And the art of mankind is the offering of its wise men, it is the adoration of the Magi, who are one with the simplest in their worship—— excerpt from the essay “The Adoration of the Magi,” from the book Essays on Art (1919), by A. Clutton-Brock (1868-1924).

Wise men, all ways of knowledge past,But they do not lose their wisdom in their wonder. When it passes into wonder, when all the knowledge and skill and passion of mankind are poured into the acknowledgment of something greater than themselves, then that acknowledgment is art, and it has a beauty which may be envied by the natural beauty of God Himself.

To the Shepherd's wonder come at last.

Sunday, January 06, 2013

Epiphany

Three Magi adoring the Christ child, at the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis.

A description of the Magi, attributed to the Venerable Bede:

Magi sunt, qui munera Domino dederunt: primus fuisse dicitur Melchior, senex et canus, barba prolixa et capillis, tunica hyacinthina, sagoque mileno, et calceamentis hyacinthino et albo mixto opere, pro mitrario varia compositionis indutus: aurum obtulit regi Domino. Secundus, nomine Caspar, juvenis imberbis, rubicundus, mylenica tunica, sago rubco, calceamentis hyacinthinis vestitus: thure quasi Deo oblatione digna, Deum honorabat. Tertius, fuscus, integre barbatus, Balthasar nomine, habens tunicam rubeam, albo vario, calceamentis milenicis amictus: per myrrham Filium hominis moriturum professus est. Omnia autem vestimenta eorum Syriaca sunt.Elsewhere, St. Bede wrote that one Magi was European, another African, and the third Asian. A mosaic at a fifth century church in Ravenna gives their names as Balthassar, Melchior, and Gaspar.

God's message, once limited to his Chosen People, became public and universal for all the nations, and so Epiphany has been called the most Catholic — or universal — of all feasts. Besides Christ's manifestation before the Magi, this feast day also traditionally celebrates the Nativity of Christ, the baptism of Christ in the Jordan River, and the wedding feast at Cana, where Christ turned water into wine.

Thursday, January 03, 2013

Christmas and Cartesian Dualism

ONE OF THE CORE principles of modernism is ‘Cartesian dualism,’ the philosophical theory that the spiritual mind of man is divorced from the material human body. We see the practical results of the belief in this divorce in political practice, where material concerns are tightly and comprehensively regulated by the state, while the soul is seen as being completely free from all considerations, even regarding morality, which we find in political rhetoric considering freedoms and rights. According to the notorious ‘mystery passage’ of the Casey decision, the Supreme Court of the United States stated: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life”; Besides being metaphysically absurd, this passage has been subsequently used to devise novel rights.

The fact that people do make up various theories of the meaning of life should not mean that all these theories are right: we are all free to make up our own theories of gravitation, but we know that there are very few theories of gravity that are even close to be plausibly correct. The orthodox view instead sees the material body and spiritual soul integrated into the human person; in the order of creation, we sit midway between the purely material animals and the purely spiritual angels.

It is quite odd, but it is quite common for men of science — pure materialists, one would think — to be attached to strange, occult and unorthodox spiritualism. Perhaps this is a consequence of the modern divorce between the soul and body.

Modern Cartesian man often has a feeling of unreality; he feels that he is a ghost wandering in a material cosmos, for that is a consequences of the theory that we are ghosts in a machine. But we know that we are one person, and not two. It has been noticed that there are some circumstances when modern men snap back into reality, when they realize who they are. The late southern Catholic writer, Walker Percy, noted that both sex and violence pull us back into the real; the normal Cartesian disembodied state snaps back into reality when something really important happens, especially if that something is violent, cataclysmic, or involves the basest of animal passions.

Everyone who remembers the attack on Pearl Harbor, or the assassination of President Kennedy, or the destruction of the World Trade towers, or times of more personal tragedy, can likely recall in vivid detail what they were doing at that time when they first heard of the news. They, suddenly, were pulled back into what is real. In the aftermath of such disasters, all that is truly good in human nature suddenly flourishes: people show love and concern for each other, people appreciate what they have, they see the world about themselves with a new clarity; drug addicts no longer feel the need to get a fix, and abortionists have no clients.

Sadly, this clarity of life and the new appreciation of reality does not last, and modern men go back into their disembodied, ghostly Cartesian state. But perversely, this means that people look forward to the next disaster because it makes them feel real. Percy argues that this is the reason why people are fascinated by news reports on tragedies, and I suspect this may be a reason why people find end-of-the-world predictions so compelling or even desirable. This can lead to gnostic-like thinking, where people are so alienated from the material world that they seek to chastise or even destroy it.

The Church has always been inflexible in holding to the doctrine of the Trinity, because it is the center of our Faith. But it is also psychologically necessary: the season of Christmas reminds us in a vivid, concrete way that Christ is God Who took on human flesh to save us. The material world is not a mistake, but was made very good; its is not a prison house for the soul but is an essential part of what we are; although fallen it has been sanctified.

One of the delights of the Catholic faith is its liturgical year, and its cycle of festivals, where one mystery of the faith is celebrated on one day, and other mysteries are celebrated on other days or during other seasons. But some modernist theologians insist that all of the mysteries ought to be celebrated simultaneously, all of the time, as if a Christian would forget about Good Friday on Christmas Eve. But does this not seem excessively spiritualistic, denying the right ordering of things in time? Is this a sign of the modern Cartesian mentality?

The public festivity of religious holidays therefore signals an orthodox understanding of the importance of the material world.