I HAD A BRIEF

I HAD A BRIEF conversation with a Catholic theologian, and we were talking about art; we both were somewhat puzzled by how very little can be found in the way of formal Catholic art theory; the last word, it seems, is

Art and Scholasticism by

Jacques Maritain, and that book dates from 1920-1935.

The amount of theoretical writing on the subject of art in sacred scripture, or by the Saints, Fathers and Doctors of the Church, the Popes and the bishops, clergy and religious, or theologians is apparently slight. There is no compendium of the artistic doctrine of the Church. This is strange, especially considering the great artistic patrimony of the Church.

But we ought not be surprised, for what we have is enough. Foremost is the great Catholic artistic tradition itself: it speaks for itself and ought not need any apology.

But self-conscious philosophical writings on aesthetics starting popping up during the Renaissance, by men who were more conformed to the world and the flesh rather than to Christ. The Iconographic and Gothic styles of church art, despite being successfully employed for centuries, were quickly rejected because no one could intellectually defend them.

With my own eyes I have seen hundreds of books on art theory at

Washington University's

Art and Architecture library, the vast bulk of which is on the art styles of the past century. So much is written on so little — quite the opposite of what we find with liturgical art. But the modernist theories are usually based on the systems of Kant, Hegel, Marx, and sometimes Freud: these are heresies and cannot be the basis for an authentic Catholic art.

Anyone who would be foolish enough to oppose Modernist art could be counterattacked with an vast array of intellectual weapons, as well as suffer

ad hominem attacks such as being called a philistine. A Catholic artist or a Catholic patron of the arts therefore finds it hard to

justify, intellectually and personally, an authentic Catholic style of art. This is a difficult situation.

The most common Catholic response is capitulation. A contemporary Catholic church may show little that is distinctively Catholic either inside or out. We live in a time where the faithful work long hours, pay high taxes, suffer from the decline of Catholic schools, and are constantly propagandized by the mainstream media, so what alternative do we have? Our culture strongly encourages or forces a certain kind of conformity.

There have been attempts to ‘baptize’ art forms, and some adaptations have been more successful than others. We are beginning to understand how influential the Jewish Temple and synagogues were to early Christians in forming liturgical worship, art, and architecture. The Romanesque likewise worked very well for Christian worship, despite its pagan roots, and there are many local traditions that flow out of the local artistic customs — as we see with Celtic art, or the arts of Asia. Shawn Tribe and Matthew Alderman write about ‘

The Other Modern’ — a now-defuct movement to aggressively Christianize the otherwise secular Modernist styles. This movement died out in the 1960s, but it provided Catholic art and architecture which is sometimes very good. But a purely iconoclastic modernism is not acceptable, and I find it hard to justify the ‘baptism’ of some more recent artistic trends — their artists need to be baptized first. As Saint John Vianney once recommended, a pastor ought to strengthen the faithful in his flock, helping

them to evangelize their heathen neighbors; likewise a Catholic artist or art patron ought to first strengthen the authentically Catholic arts and artists, helping them to evangelize the world.

When I visited the Washington University art and architecture library, I was seeking books that described the roots of the classical tradition — the tradition that came up from ancient Greece and Rome, and the Christianization of the tradition in Catholic Europe of the Middle Ages; I was also interested in the roots of the traditions in other cultures, such as China, India, and Japan. First things first: this seemed relevant to my enjoyment of traditional Catholic church architecture and I wanted to know how it can be intellectually justified. Before I started my research, I emailed some prominent educators in the tradition; and they replied that not much in the way of theoretical art writings were available: Vitruvius was the primary intellectual source from antiquity. I went to the library searching for commentaries

about Vitruvius (I already had a copy of his

Ten Books on Architecture, purchased long before I became Catholic.) Oddly enough, the first book I saw on the bookshelves was Maritain's

Art and Scholasticism; this immediately seemed important to me, and I copied out significant passages.

Vitruvius himself tells us the roots of his (and ultimately our) tradition, although it is easy to skip over that section in his work; he describes the education of an architect, and that education is the schools of Pythagorus, Socrates, and their followers. In these schools we thankfully do not learn much about the demonic pagan gods, nor do we fall into the skepticism, deceit, and power-mongering of Socrates' enemies the Sophists. Rather we learn about beauty, harmony, justice, virtue, and love, and the One true unknown God who is the ultimate Source of all good things. When we marry this philosophy with the religion of the Jews and the revelation of Christ, we get the Catholic intellectual tradition.

I pursued this research into the roots of the Catholic artistic tradition for a while until the illness and untimely death of a girlfriend led me to abandon it, and instead I went on a prolonged pilgrimage to many churches, whose photos can be seen on this blog.

My photography of churches is easy, because I merely try to represent their inherent beauty in an image.

(Please accept my apologies for not posting more photos of churches lately; I've been very busy with some projects and gasoline is expensive.) Recently I've gotten commissions to take photos that are more landscapes; I find this very difficult because a natural landscape does not naturally have a good composition — despite what the Impressionists say — and so I have to go back to the basics: what is beauty? Why is something beautiful? So I am going back to the roots of the tradition, learning the basics of proportion and symmetry which lead to the perception of beauty.

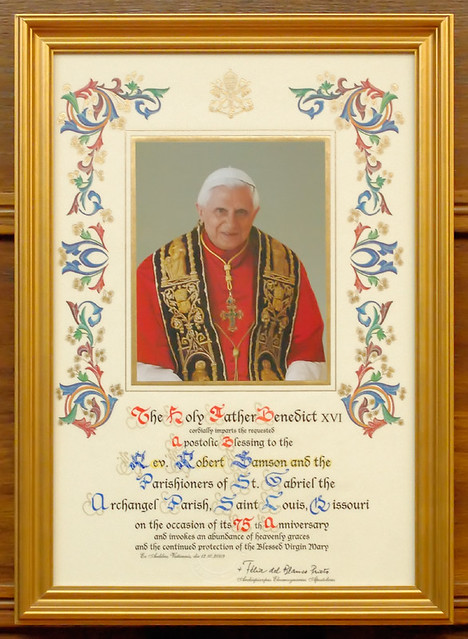

The iconographic tradition relies strongly on proportion and harmony, and is making a resurgence lately, not only in the East but also in the Latin Church. There are two main reasons for this: Pope Benedict XVI highly recommends it, as is seen in his book

The Spirit of the Liturgy; also consider the fact that an artist can actually learn this living tradition from active iconographers. On the other hand, a contemporary artist who wishes to learn the Gothic must most likely reconstruct the tradition from historical sources; while there may be some workshops in some places that maintain ancient Gothic churches, I am not aware of any art or architecture schools that teach the practical tradition of the Gothic style.

We are fortunate enough to have a large body of existing Catholic art and architecture, worthy for devotion and liturgy, and which may be used by contemporary artists as inspiration for their own work. But even when we have examples, we still cannot easily use these as prototypes for new work unless we know the design principles behind them. Suppose we need to adapt an existing design, for example, we need to add a door in a particular wall; if we do not have an existing example of this sort of thing, then we risk producing a modification that appears disharmonious. But if we know the

principles behind the design, then we can create the modification in a way that looks authentic and harmonious. Even something as simple as a Gothic arch or rose window can look ridiculous if the designer doesn't know the principles behind its geometric construction — and I've seen many odd imitations. So an artist must not only be familiar with older art and be able to imitate it, but rather ought to know its construction. Knowing the design behind the design will give an artist great flexibility.

So we must be aware that the living Catholic artistic tradition resides in the artists themselves far more than in books of art theory, and that these artists may or may not hand down the traditions to new generations. Sadly, there have been several times in history when this handing-down was lost or nearly lost: such as the end of the Gothic era that occurred because of the Reformation, and when the Baroque academies were shut down by revolutionaries. Because of the risk of the loss of continuity, writing some things down is very important, but this writing is likely to be found more in trade journals (and now websites) rather than in magisterial documents.

The living tradition also is handed down through the Bishops and their priests; for it is they who primarily commission churches and their furnishings. They, more than any artist working in a studio, will likely know of what art is effective for spurring on the faith and what is not. But even a bishop cannot act in a vacuum, for it is the laity who pays for this art and architecture. And so we can conclude that artists, clergy, and the laity all ought to move towards the same goal.

It turns out that

Art and Scholasticism is not the last word in Catholic art theory; indeed Maritain (who was a close friend of Pope Paul VI) is known for having ended up on the side of Picasso and modernism. A critique of Maritain can be found in the book

Aesthetics by

Dietrich von Hildebrand (who was a friend of Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI). Unfortunately this book is not found in an English translation. However, we must keep in mind that Catholic art is more important than Catholic art theory, and that faith is more important than art.

Disharmony is often seen in the arts these days, but these arts have revolutionary purpose, and as we see very clearly now, the goal of this revolution is death. But the idea of life-giving harmony is found not only in what is left of the Western tradition but also in the ancient traditions of the far East and elsewhere, and so these principles are very likely universal on a natural human level. But a Catholic artist must build upon the natural law and delve deeply into revelation and prayer in union with the Church. I've seen churches which were designed around prayers such as the Litany of Loreto or the Rosary, or the Sermon on the Mount, or a Psalm. And so the foundations of an authentic Catholic art style must include the stones of the universal human tradition and the liturgy and doctrine of the Universal Church, as well as the living stones of Catholic artists and art patrons.