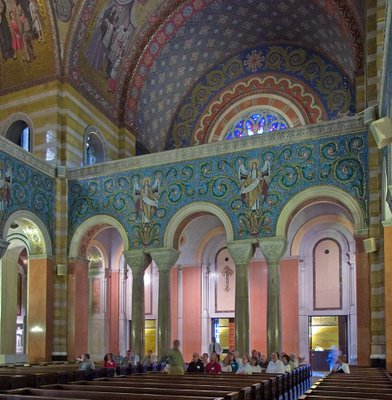

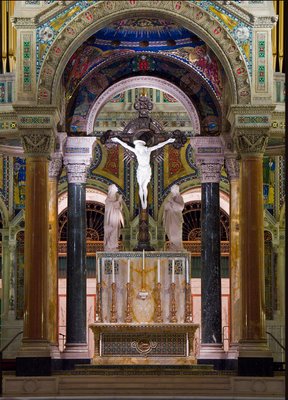

Until quite modern times - I think, until the time of the Romantics - nobody ever suggested that literature and the arts were an end in themselves. They "belonged to the ornamental part of life," the provided "innocent diversion"; or else the "refined our manners" or "incited us to virtue" or glorified the gods. The great music had been written for Masses, the great pictures painted to fill up a space on the wall of a noble patron's diningroom or to kindle devotion in a church; the great tragedies were produced either by a religious poets in honour of Dionysus or by commercial poets to entertain Londoners on half-holidays.The arts today are a horrible mess. Just look at the Wikipedia article on Art to see the principal of First and Second things in action:

It was only in the nineteenth century that we became aware of the full dignity of art. We began to "take it seriously" as the Nazis take mythology seriously. But the result seems to have been a dislocation of the aesthetic life in which little is left for us but high-minded works which fewer and fewer people want to read or hear or see, and "popular" works of which both those who make them and those who enjoy them are half ashamed. Just like the Nazis, by valuing too highly a real, but subordinate good, we have come near to losing that good itself.

How best to define the term "art" is a subject of much contention; many books and journal articles have been published arguing over even the basics of what we mean by the term "art" (Davies, 1991 and Carroll, 2000). Theodor Adorno claimed in 1969 "It is self-evident that nothing concerning art is self-evident any more." (Danto, 2003). Indeed, it is not even clear anymore who has the right to define art. Artists, philosophers, anthropologists, and psychologists all use the notion of art in their respective fields, and give it operational definitions that are not very similar to each others.The confusion here continues:

Many have argued that it is a mistake to even try to define art or beauty, that they have no essence, and so can have no definition....The classical definition of art is "the virtue of making things well". It is a virtue, that is, a good habit of a person, and what is produced by that virtue is an object of art. By this definition, nearly everything in life is art. The modern definition of art, what is called "art for art's sake", has ruined all art, by making art a meaningless concept. It elevates a narrow slice of all art above the rest, and all art is lost in the process. Making something for a utilitarian purpose nowadays almost certainly means giving it a utililitarian (and ugly) design, since a useful object cannot possibly be 'art' to the modern, elite, mind. Even Wikipedia's sole rejection of "art for art's sake" is Marxist and promotes utilitarianism, and not practical beauty.

Another approach is to say that "art" is basically a sociological category, that whatever art schools and museums, and artists get away with is considered art regardless of formal definitions.

Proceduralists often suggest that it is the process by which a work of art is created or viewed that makes it, art, not any inherent feature of an object, or how well received it is by the institutions of the art world after its introduction to society at large....

Functionalists, like Monroe Beardsley argue that whether or not a piece counts as art depends on what function it plays in a particular context, the same Greek vase may play a non-artistic function in one context (carrying wine), and an artistic function in another context (helping us to appreciate the beauty of the human figure).

Often one of the defining characteristics of fine art as opposed to applied art, is the absence of any clear usefulness or utilitarian value. But this requirement is sometimes criticized as being a class prejudice against labor and utility....

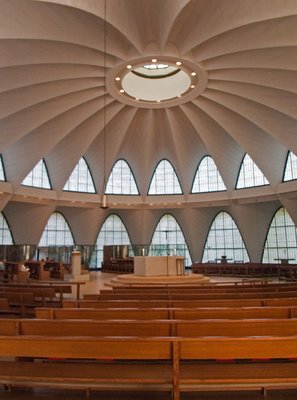

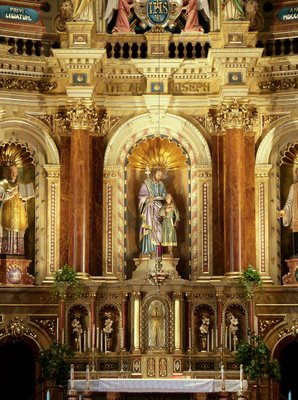

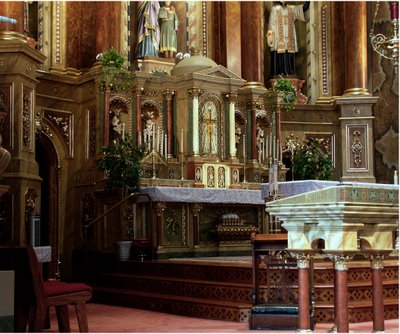

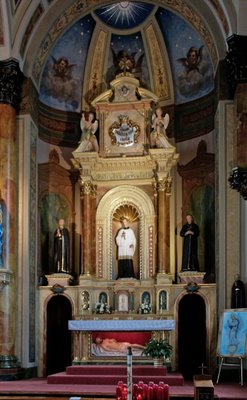

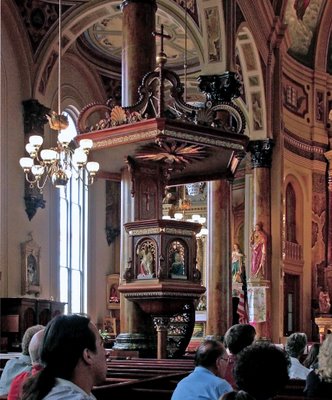

Just go to a large art museum, which has a diverse collection of artworks from various time periods and cultures. Invariably, those works that were made for their own sake, as ends in themselves (which will invariably be the most contemporary objects in the museum), will usually be ugly, and we will inevitably be told that we should ignore our preconceptions of beauty. The older works of art, made for a church, temple, or for the pleasure of a patron or as a public monument, and never for its own sake, will almost invariably be beautiful. Even ancient objects from radically different cultures, like China, India, Islam, Egypt, and so forth, are almost universally acclaimed to be beautiful, and those cultures did not accept our modern notion of putting the Second Thing of "art for its own sake" first.

AFTERNOTE: Today (Aug. 6, 2006), It struck me: "Art for Art's Sake" is idolatry: elevating a creature above all else.