Here is Assumption Greek Orthodox Church, in Town and Country, Missouri, located about 17 highway miles west of downtown Saint Louis, Missouri.

The church was built in the late 1970s, and has a somewhat nondescript appearance from the outside. But we have to take a look inside!

Right inside of the narthex is this elaborate wood carving of peacocks, a theme that is repeated throughout the church. Peacocks symbolize resurrection, immortality, and the omniscience of God. The notion of peacocks symbolizing pride is a recent Western invention.

This is illumined by light coming from a stained glass window.

Since my knowledge of Eastern Christianity is weak, I probably am getting some of my descriptions wrong, and I tend to use Latin terms, so please bear with me.

Votive candles; both tapers fixed in sand, and the more familiar glass-encased candles. This is a tradition that goes back to the Jewish Temple.

Icons in the narthex.

Icons of the anastasis, or resurrection. These photos were taken during the Easter season.

From what I can guess, these are icons of the Emperor Constantine (baptized on his deathbed) and his mother Helena; Saint Joseph; the twin physician martyrs, Saints Cosmas and Damian; and the Koimisis, or Dormition of the Virgin Mary.

The veneration of icons is a distinctively Eastern Christian practice, although ironically, it was a Byzantine Emperor who started the iconoclast controversy, while the Pope in Rome defended the practice. Very few ancient icons still exist, due the persecution by the Emperor. However, we are fortunate to have many copies of older works as well as the notebooks of some artist-monks.

Tradition tells us that the very first icon was of Mary and Jesus, and was painted by Saint Luke the Evangelist; subsequent iconography copies this style, and the work tends to be an organic development of the ancient Greek tradition of painting. We also have an ancient image, the acheiropoietos, of Jesus, which tradition says was done from life, as well as the image on the Shroud of Turin and His burial face-cloth. Icons are not done in a realistic style, because we are not interested in bodily beauty, but rather in spiritual truth.

To understand the theology of icons, we need to know about the philosophical theory of forms, ideals, or archetypes that comes originally from the writings of Plato. A material object is merely a shadow, reflection, or image (Greek: eikon, icon) of the eternal, unchanging form of a thing. For example, we can draw or build triangles of all sorts, but they are not real triangles: the ideal triangle, or form of a triangle, is the unchanging and eternal essence of triangleness, in which material triangles imperfectly participate. Likewise, the icon, or image of a Saint, participates in the unchanging, eternal form of the Saint who is in Heaven. So an icon is a window to Heaven.

Perspective in icons, if present at all, is inverted; instead of the vanishing point being logically a place beyond the surface of the painting, it is inverted to be inside of the viewer. This comes from the deep, Western form of mysticism originating in the Neoplatonic school, where a virtuous mystic seeks the Holy Spirit within himself through contemplation.

Eastern iconography rejects the modern Western notion of "art for art's sake", and instead sees art as a virtue. An icon painter needs to be a holy mystic, full of virtue. "Creativity", a concept that comes from Marxism, is also rejected, and instead iconography is highly traditional and is bound by canon law.

The Orthodox liturgy comprises all of the senses, and the veneration of icons—which include prayer, burning candles, bows, kiss, or incense—also incorporates the sense of touch. The veneration (proskynesis) of icons is not worship (which is due to God alone), and is only relative, passing on to he who is depicted on it: to its prototype.

It should be noted that the Platonic philosophy used to describe icons is rejected by Protestants and Liberal religion in general; so veneration of icons, to these, is incomprehensible. However, Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI), in his book, The Spirit of the Liturgy, teaches that the Orthodox theology of icons is normative for the Catholic Church. Typically, the Latin Church is semi-iconoclastic, that is, icons are not directly venerated, while Protestants and Liberal religionists are iconoclastic, if not smashing, then at least avoiding images.

The Blessed Virgin Mary and the Christ child. In Orthodox iconography, I've read that Mary is never represented without Jesus. This icon is 'dressed' with only the painted faces showing; often this 'dress' can be easily changed.

The interior of the church, during Vespers. Icons cover the ceiling.

A priest chanting Vespers at the altar. As in the Latin Church, he incensed the altar during the Magnificat. He is facing the altar ad orientem, which also happens to be the geographical east; this was also the norm in the West before Vatican II: all worshippers, including the priest, face Christ.

The chanting here was beautifully done. I've never heard any of the Hours done in a church before.

The liturgy here is in the vernacular, and the prayers were strikingly familiar, seemingly identical to the Catholic Liturgy of the Hours from the reforms after the Second Vatican Council (but with lots of additional prayers). Apparently, Orthodox English translations are adaptations of the Anglican liturgy in the Book of Common Prayer. But the Anglicans got their current translations from the International Commission on English in the Liturgy, or ICEL, which is a very ecumenically-minded organization of English-speaking Roman Catholic bishops. But like the Catholic Church, the Orthodox rejected the ICEL's proposed version of the Lord's Prayer, and use the familiar Cranmer's Anglican version instead ("Our Father who art in Heaven, Hallowed be Thy Name...."), which is very beautiful and is only slightly mistranslated from the Greek.

Saints Kyriaki (or Dominica) and Irene, martyrs.

Following are ceiling icons. The church sells greeting cards with high-quality photos of these icons for fundraising.

The Apokathelosis ("Un-nailing"), or Christ being taken down from the Cross. Underneath the Cross is the tomb of Adam; Christ is the New Adam.

The Apokathelosis is solemnly remembered during the Vespers for Great (Good) Friday.

The large icon depicts the Dormition ("falling asleep") of the Blessed Virgin Mary, surrounded by the Apostles, which took place about a decade after the Crucifixion. This is called the Assumption in the Western Church. The feastday is universally celebrated on August 15th in both the East and West.

The Kathodos ("way down"), or Christ's descent into Hades, to rescue the souls of the just. The Western Church tends to depict Christ leaving the tomb.

Many Saints.

The Cross is empty. Crucifixes do occur in Orthodox churches, but they tend to be small.

This looks like a bishop's chair (although this is not a cathedral). On the back is a depiction of Christ as King.

The iconostasis, separating the nave from the sanctuary, and decorated with icons (some of which, I've been told elsewhere, typically can be changed according to season and feast). The altar is behind a door in the center. This form, a solid wall separating the priest from the people, developed in the 14th century; previously curtains topped by icons veiled the sanctuary. Rood screens were the equivalent feature in Latin Christianity, but many were destroyed during the Reformation. Since the Baroque period, Catholic churches have omitted this traditional element, under the influence of the Jesuits who wished to promote the active participation of the faithful in the Mass.

The iconostasis harkens back to the veil covering the holy of holies in the ancient Jewish Temple at Jerusalem. This area was exclusively reserved to the High Priest, and housed the Ark of the Covenant, containing the Word of God, Manna from Heaven, and the Rod of Jesse. Since that happens to be precisely what is contained in the tabernacle here, it is entirely appropriate that it be housed in a contemporary sanctuary reserved to the priests. The veil in the Temple was torn at the Crucifixion, so likewise the iconostasis is opened to allow Christ to come to us in the Eucharist.

Christ is depicted in the icon on the left: he is identified in iconography by the Greek letter monogram "IC XC", for Jesus Christ.

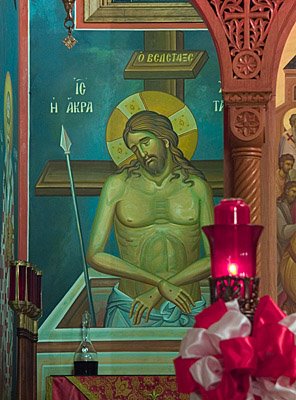

The Akra Tapeinosis ("utmost humiliation"), or Man of Sorrows, located behind the iconostasis. The dead Christ being put into the tomb.

The altar is behind this opening in the iconostasis. Here, as according to tradition, is the icon of the Virgin Mary to the left, and Christ to the right. Above the door is the Last Supper.

The altar. The ribbons say Christos Anesti, Christ is Risen.

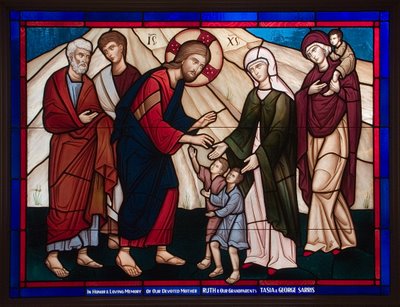

A stained glass window in the school building.

Flags of Greece, Missouri, and the United States.

Much thanks to Father Joseph Strzelecki, who kindly gave me permission to photograph in his church.

This upcoming weekend is the Latin Liturgy Association convention. On Friday, the convention will host a church tour, which will include a visit to Saint Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church in Saint Louis, Missouri.

Simply amazing! Why can't Catholic churches built in the 1970's look like that? I find it interesting the church has pews. Many Orthodox churches (especially the more traditional ones) require everyone to stand the entire time (and some, like where my girlfriend's parents go, require men on the right side and women to stand on the left). Here's a trivia question for you: Do you know what the difference is between the candles lit and placed in the sand and those lit and placed in a stand/glass?

ReplyDeleteYCSTL:

ReplyDeleteQ: "Why can't Catholic churches built in the 1970's look like that?"

A: Do you want a nice, but wimpy answer; an extremely uncharitable answer close to the raw truth; or a nuaced, critical analysis of the problem? Ha ha.

I have been in, I think, four Orthodox churches in my entire life, all in this area, and three of the four have pews.

I have no idea what the difference in candles might be. What is it?

Maybe we should just skip the answer to the first question...

ReplyDeleteAnswer to the candle question: The candles placed in the sand are lit for the dead. The candles placed in the stand/glass are lit for the living. In the more traditional churches (where you wouldn't find pews), you light the candles on the right side of the church for men, and light candles on the left side for women.

Proper entrance to the church (when there for more than vespers) would require kissing all of the icons placed in the middle of the church, kissing the candle(s) one is about to light, crossing oneself, and then lighting the candle either for the dead or living.

The traditions of the Orthodox faith are simply fascinating.

I should have asked -- which one didn't have pews?

ReplyDeleteSaint John Chrysostom Russian Orthodox Church, in House Springs, Missouri did not have pews. This particular church is made up mainly of recent Russian immigrants.

ReplyDeletesimply lovely.

ReplyDeleteyeah, the pews make it hard for you to bow and touch the floor for the signing during the Epiklesis where you make a sign of the cross over your whole body.

I have been to every Orthodox church in the St. Louis area and this is the most beautiful of them all. Everyone must see it. You have the same experience as seeing the Cathederal Basilica in that you can not take your eyes off the ceiling and the gorgeous Iconostasis. One orthodox church that does dot have pews is St. Basil the Great Russian Orthodox on McCausland in south St.Louis. It is a charming little, traditional Orthodox church that I highly recommend

ReplyDelete